Game design is a craft learned through shared experience, not just theory. Our Designer Spotlight series features creators at every stage, from hobbyists testing their first prototype to established professionals juggling studio pipelines, because every perspective teaches something different.

This time: a solo publisher running design, marketing, and art direction between shifts at a steel mill. Chris Eastridge proves you don't need a team or a trust fund to build a catalog. You need systems, speed, and the wisdom to know when a project isn't working.

From Video Screens to Cardboard Dreams

Chris Eastridge is a process automation engineer at a steel mill, an Air Force veteran, and the sole operator behind Moon Saga Workshop. He handles design, publication, marketing, and art direction himself, collaborating with consultants and playtesters but running all operations solo.

His path to tabletop started in 2012 with video game development. He'd prototype digital ideas using paper and cardboard to work out mechanics before writing any code. Somewhere along the way, the prototypes became more interesting than the software they were meant to inform.

"After publishing a couple things on the Play Store, I realized I had an affinity for the tactile nature of the design process," Chris explains.

The cardboard stopped being a stepping stone. It became the destination.

Fail Faster, Document Everything

Chris's design philosophy comes down to two words: fail faster.

His prototypes are deliberately crude. Cards don't read "Bird," "Bear," or "Frog." They read "A," "B," "C." No art. No polish. Just enough structure to test whether an idea works.

"Crude components and abstracted concepts are key," he says. "Getting feedback immediately matters more than making it pretty first."

But speed without structure is just chaos. Chris follows what he calls the innovation engineering method: Plan, Do, Study, Act. Every iteration gets documented. Every version tells a story. What looks like a pile of failed prototypes is actually a diary of decisions.

"The failed iterations are now just documented diaries!"

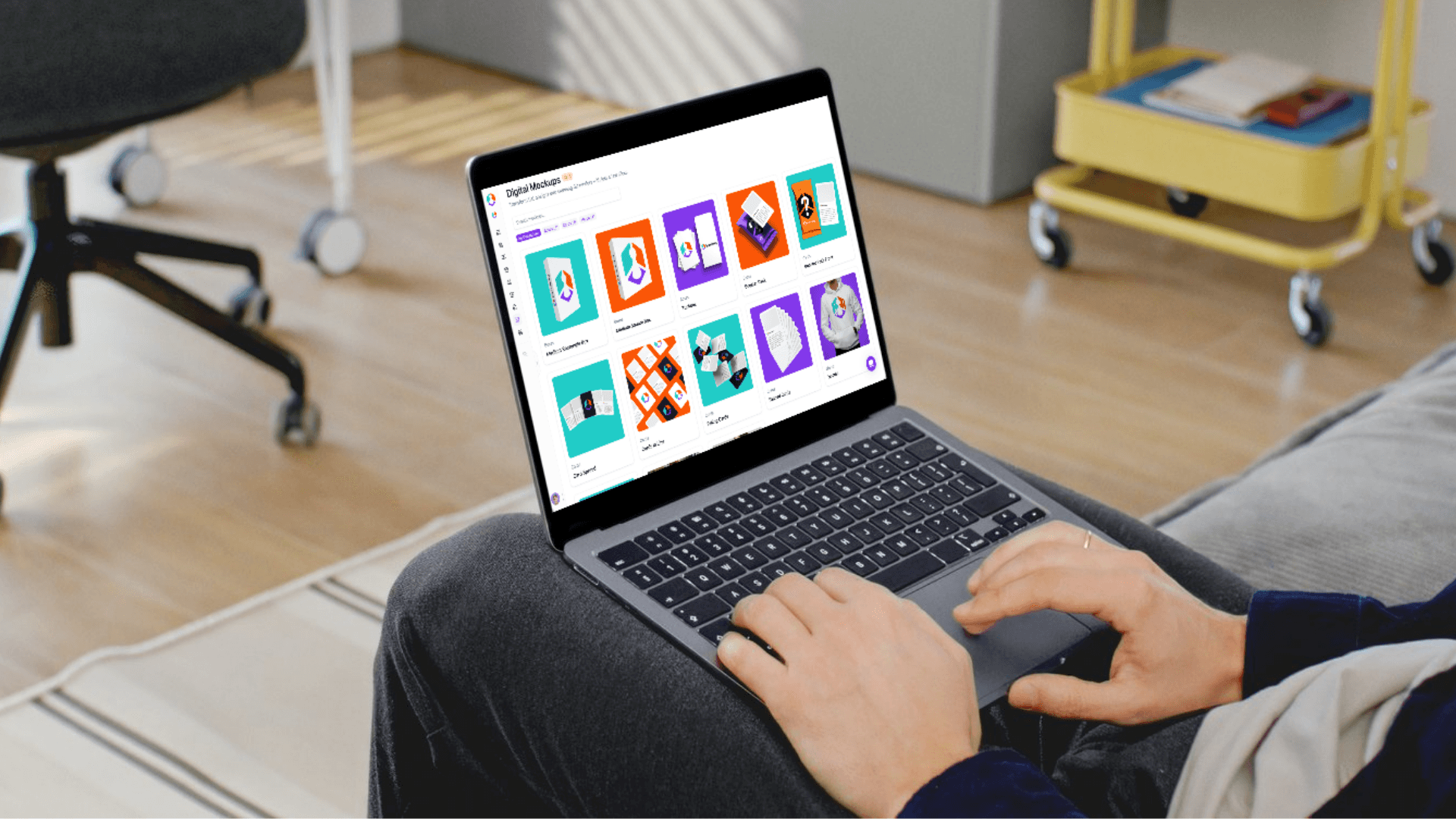

This is where Boardssey fits into his workflow.

"Boardssey has helped me by giving me so many tools that makes it possible to complete "boilerplate" processes. Everything in one place makes it easy to keep your content organized and impactful. Task management is also really solid."

For a solo publisher juggling multiple projects, task management and version tracking aren't luxuries. They're how he keeps momentum across a catalog without losing context on any single game.

His favorite feature? The 3D Mockups tool.

"Render tool. That alone is worth the price of a subscription. And that sell sheet designer? Insane value."

For a solo publisher handling his own marketing, these tools close a gap that used to require outside help. The 3D Mockups turn flat card art into professional product shots. The Sell Sheet Designer means pitch materials don't require a graphic designer. Both let Chris move from prototype to pitch without leaving the platform or breaking momentum.

Parks & Potions: The Game That Taught Him Pace

Chris's first published title, Parks & Potions, started life as a video game concept called Color Combo. It found its true form on the tabletop.

In Parks & Potions, players race to brew magical concoctions using simultaneous dice rolling. Everyone plays at once. No waiting for your turn. No checking your phone while someone else deliberates.

The game uses simultaneous dice rolling. Everyone plays at once. No waiting for your turn. No checking your phone while someone else deliberates.

This wasn't accidental. Chris kept seeing games where scoring takes as long as playing, leaving everyone deflated at the end. Parks & Potions was his answer: keep the pace fast, keep every moment active.

It's the clearest expression of his design philosophy: if players aren't engaged during their turns, something is broken.

Building a Catalog, Not Just a Game

Chris isn't just designing games. He's building a publishing company.

"Currently planning to launch 3 new titles simultaneously," he notes. It's an ambitious goal for a solo operation, but necessary if you want shelf space at major retailers. Distributors want catalogs, not one-offs.

Part of that expansion involves localization. Chris is working with Grok Games to bring Aiye, a game originally published in Brazil, to English-speaking markets. It's a way to grow quickly without designing everything from scratch.

Of course, timing is everything. Manufacturing delays around Chinese Lunar New Year can derail an entire release schedule. Building a catalog means thinking like a publisher, not just a designer.

Currently in development:

Viking Submarine (yes, really)

5 Alarm: Chili Cook Off

Wishing Whales

Saharan Sands, a Parks & Potions expansion

All gateway to gateway-plus games. Push your luck, set collection, resource management. Smooth, approachable, and designed to respect players' time. Each one is a step toward the catalog size that gets distributors to return your calls.

Why Small Games Are Harder

When asked about trends that excite him, Chris doesn't point to sprawling campaigns or heavy euros. He points to smaller games.

"I firmly believe making small games is harder to accomplish well than more complex games," he says. "The design has to be smooth with a solid core that isn't shrouded by bells and whistles."

It echoes his design hero, Ryan Laukat, known for elegant, cohesive designs where every piece earns its place.

His most underrated mechanic? "Ability activation through placement and removal." His dream project? A nature fantasy narrative where players discover the world as they play.

Finding Your Playtesters

Chris takes a targeted approach to feedback. Designer input is useful, but his real attention goes to the players he actually built the game for.

"I usually find people who I can visualize as being in the target demographic for the game," he explains. "They're ultimately who I pay attention to the most."

The people who will buy and play your game? Those are the voices that shape the final product.

Knowing When to Fold

Running a one-person publishing company while working full-time means Chris has more ideas than hours. He's honest about the tension.

"I have recency bias and tend to drop a lot of projects and eventually get back to them," he admits.

It's the flip side of creative energy. When ideas come faster than time allows, knowing which projects to pause (and which to abandon) becomes its own skill. Not every prototype deserves to become a product.

Sometimes the smartest design decision is recognizing when a concept isn't working and walking away.

Advice for New Designers

Chris's parting wisdom:

"Don't be afraid of failure or making mistakes. If you don't take risks, you'll never learn."

And if you're self-publishing? "Fail faster. It's the fastest way to success."

Know when to push forward. Know when to fold. But never stop moving.

Follow Chris's Journey

Moon Saga Workshop: moonsagaws.com

Social: @moonsagaws

Published Work: Parks & Potions

What's a project you held onto too long? Or one you folded too early? Designer Spotlight celebrates the craft through the people who practice it, and we'd love to hear your story.